Editor’s Note: From Latin America to Central Africa, Serge medical missionaries treat patients, train national doctors, and testify to the love of Jesus. But in communities of overwhelming need and limited resources, Serge missionaries see medical research as mission as an exciting way to help transform communities.

——————-

Nurse practitioner Abigail Nelson calls diabetes the “least sexy disease to study” but one that Serge’s medical missionaries in Guatemala City are driven to know more about.

Her patients, many of whom were displaced a generation ago in the country’s 36-year civil war, live and work in slums surrounding the largest urban landfill in Central America, right in Guatemala City.

Over 13,000 people live in the neighborhood, depending on the dump for scraps of food, discarded clothing, and pieces of trash to sell to recyclers.

In this context, how does one properly treat a disease like diabetes?

In Guatemala, more than 60% of the total population has either type 2 diabetes or pre-diabetes, and well-researched treatments are often not accessible. And even well-known causes may not apply. Unlike in the U.S., type 2 diabetes in Guatemala is not as strongly linked to obesity and the causes are not fully understood.

What we do know about the disease is the effect: it plunges families deeper into poverty and devastates communities.

A New Opportunity to Serve

The Lord called missionaries Abbie and Jeff Nelson to long-term missions service in Guatemala, the most populous and poorest country in Central America, in 2018, with a passion for gospel renewal and the health of impoverished communities.

Serge Missionary Abbie Nelson with a patient

“I came here to work alongside the National Department of Health and to learn from and serve those who are on the margins of society. We hoped to see health markers improve while sharing Jesus, and providing care that directly improves lives.”

“When I got here they told me ‘Please do something with diabetes.’ Abbie says “But when I went to look for the research on best practices in this particular community… it was a long hunt for a very short list. There really is nothing.”

For all the reams of research on diabetes, the treatments assume access to a specific diet. Or consistent access to heart and kidney medication, and, if necessary, access to dialysis.”

But in this community, standard diabetes research and treatments might as well not exist.

Abbie sees the need to ask new questions, like: how can we provide excellent medical care for people with diabetes with the resources that we do have?

Because of this, Abbie sees expanding medical mission work to include medical research as a new and innovative way to model the love of the God who sees and knows them.

“It made me realize that missionaries need to be doing this research. Medical research not only allows us to bring a higher level of care but it also creates more opportunities to bring missionaries to the field – which expands opportunities for long-term discipleship and friendship. It’s the next expression of how we can love people here.”

Abbie believes that Guatemala has the resources to provide excellent care. “And,” she says, “if medical missionaries do this work – they will be bringing compassionate medical care to a community that greatly needs the love of Jesus.”

Impacting Communities Globally

Halfway across the world, another team of Serge missionaries is also seeing the impact medical research as mission can have on community health.

Serge’s medical team at Kibuye Hope Hospital in Burundi, where access to medical care is extremely limited, has sponsored small research projects for years while training the next generation of Burundian doctors.

Two Burundian medical students – always engaging in resourceful problem-solving!

Medical missions in rural areas has a long tradition of ingenuity – adapting techniques learned in the university to a myriad of settings on the field, where resources are much more limited.

But sometimes, as medical technology advances, even adapted techniques just aren’t workable.

Serge Burundi team member and emergency medicine physician Carlan Wendler shares an example of one missionary hospital in a neighboring country that received a CT scanner as a donation.

While the CT scanner was a useful resource, it had unintended consequences. The hospital had a huge bill for the maintenance cost. It caused the power infrastructure to frequently crumple, and the patients could not afford the scans.

Even worse, importing high-tech equipment works against the goal of training Burundian medical doctors. “The more we get away from their future practice environment, the harder it will be for them when they leave medical school,” Carlan says. “In a way, we are asking our students to return to an older form of medical diagnosis based on studying and observing.”

“That’s why we need curious people to come work with us and ask the question, ‘What do we not know and how can we find out?’ That is the appetite for research.”

Asking Life-Saving Questions

Scientific-medical research starts with a question. It could be a very general question like, “How do we treat malaria if we run out of our usual medication?” or a very specific question like, “Is it safe to perform a lumbar puncture on an AIDS patient with a CD4 count <200 in the setting of behavioral changes?” Then, you look for evidence published by others that can answer your question.

In 2018, Carlan and one of his medical students posed such a question. They wanted to know whether or not the surface area of a Burundian’s hand was really about 1% of their total body surface area.

“You see, we use the surface of the patient’s hand to estimate how extensive a burn is, especially when it is large and irregular in coverage (like a splash burn from a pot of boiling beans),” Carlan says.

There were some studies in other populations that showed hand size was variable, but almost no one had ever looked at Africans.

So, for two years, they traced the hands of hundreds of patients and collected data about their age, gender, height, and weight in order to estimate their total body surface area (TBSA) and compared the measured surface of their hands with 1% of their TBSA.

Lo and behold, it was significantly different.

“You see,” says Carlan, “overestimating the extent of a burn has serious consequences – especially in kids and especially in settings where malnutrition is a consideration, It might lead a clinician to give too much fluid in resuscitation which can lead to swelling of the brain and fluid on the lungs…neither of which is benign.” Doing this kind of research enabled Carlan and his student to share this finding with the broader community in order to save precious lives.

The greatest encouragement to publish our data.

Creating Long-Term Discipleship Opportunities

In addition to saving lives, medical research also creates a unique opportunity to bring together the call to help the sick and the call to make disciples. While working with a medical student for a one-month rotation is certainly impactful, when that student can become a partner on a multi-year study – it becomes a long-term discipleship opportunity.

Back in Guatemala, the first steps are already being taken – two American medical students with an appetite for research and for spiritual nurturing will be joining the Guatemala team as vocational interns.

They will begin to process the data that the diabetes clinic has been gathering and the team is excited for what they will help discover and the relationships that they will build as they work in the community.

Abbie is encouraged that Guatemala has a culture that would work well with research. Her patients aren’t wary or suspicious of medical practice, she says. And they have a compassionate and hard-working culture. They come up with incredibly creative solutions to problems and are open to questions.

But this is also an important avenue to share the compassion of Jesus with her patients. Because for all the upsides of Guatemalan culture, there is also a fearful and mystical misunderstanding of disease. They often think they are being punished by God.

“It’s really hard to interrupt someone’s theology,” Abigail admits. “But research done by followers of Jesus is an expression of the care God has for them, and the answers they discover can not only treat the disease but help fill in the gaps where fear and shame have created a false narrative of why people are sick.”

Abbie and Friends in Guatemala City

“There is so much we don’t understand about how to treat disease and save lives in this part of the world,” Abbie says. “And as we approach these communities with compassionate curiosity, relationships open up in the most beautiful ways, bringing opportunities for gospel renewal and healing that far exceed numbers on the page.”

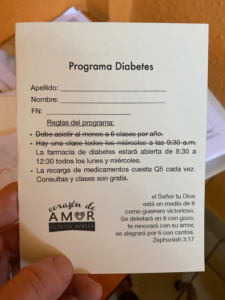

As Abbie meets with patients in her community she often prays with them and leaves her business card with a verse from Zephaniah – a reminder that Jesus sees them and loves them greatly – and is working to turn their current suffering into everlasting joy.

The appointment card Abbie gives her patients with a verse from Zephaniah.

“The Lord your God is with you,

the Mighty Warrior who saves.

He will take great delight in you;

in his love he will no longer rebuke you,

but will rejoice over you with singing.”

– Zephaniah 3:17

Take the Next Step

Do you have a passion for medical research or long to see communities transformed by the gospel through compassionate medical care? View short-term and long-term missions opportunities or give now to support the work.